-

- 05 Mar

More about Real Capital – Why capital intensive industries like mining continually fail to achieve expected returns to investment

This paper is the second in a series examining the differences between real capital and financial capital. Real Capital is to Financial Capital as Real Options are to Financial Options. Not recognizing the differences between the two leads to incorrect investment decision-making and to failure to achieve expected returns to investment. In this paper I examine asset values and the problem of asset write-downs which plague capital-intensive industry.

Background

This paper is the second in a series where I examine the differences between real capital and financial capital. Real Capital is to Financial Capital what Real Options are to Financial Options. Not recognizing the differences between the two leads to incorrect investment decision-making and to failure to achieve expected returns to investment.

The first paper in this series examined real options, and how they related to real capital. The paper highlighted how insufficient cognizance of the value (or loss in value) associated with change throughout the life of a project was a primary cause of poor capital-investment decision-making.

In this paper I examine asset values and the problem of asset write-downs which plague capital-intensive industry. Once again, unplanned-for change is the source of the trouble.

A Familiar Story

I start with a story that is just one out of probably hundreds of similar stories in most capital-intensive industry. This story is very real but its economic underpinnings get scant coverage from theory – again because most economic theory does a very poor job of understanding real capital.

This story had its genesis when the CSR Company – a respected Australian company originally in a different business – decided to exit their mining investments in the late 1980s. As part of this process, their South Blackwater Mine was sold to Pennant Holdings. The sale agreement provided for the liability for reclamation of the unrestored spoil piles and tailings dams to remain with CSR. CSR were presumably comfortable with retaining this liability because they had appropriate provisions on their books – an amount, as it turns out, of about $1 million. Unfortunately the new owner went into receivership two years later. The mine was sold again. This time the new operator adopted a new mine plan triggering a requirement for reclamation of (most) of the previously mined-out areas, so the actual cost of the reclamation liability had to be ascertained. The cost turned out to be more like $10 million – 10 times the amount provided for. Needless to say, this was not good news for CSR who thought that they had washed their hands of the mine two years before.

This example is yet another one where assets and liabilities on company books have a poor relationship to their economic value or cost, and where uneconomic and inefficient practices and the [in]correctness of provisions can go unnoticed and endure for a long time.

The example here involves no suggestion of anyone deliberately misrepresenting results for some self-serving end (although this obviously happens too). Commonly the enterprises involved are respected and experienced companies who, despite their best efforts, all-too-often get caught out under-depreciating assets, and [when viewed with the benefit of hindsight] over-reporting profits.

It is not surprising when many modern commentators, echoing Adam Smith from more than 200 years ago, see mining in such an unfavorable light. After investing the initial capital in the expectation of strong returns, the strong returns never materialize, and, not only that, previously presented profits turn out to be illusory because of unexpected write-downs.

In this paper I examine asset valuation. In boom times and when all aspects of an investment are proceeding according to plan (when there is no requirement for plan revision) then short-comings in asset valuation are unlikely to be noticed. However in commodity price downturns (requiring plan revision) and through mergers, restructurings, and acquisitions the short-comings in asset valuation are exposed. The challenge is to develop and apply formulae or other guidelines that leave no uncertainty in this area.

The bad news is that it cannot be done. I explain why.

Asset Valuation

Asset valuation is not a problem when a project is new.

Similarly, if the project proceeds according to plan there is seldom a problem – the asset gets disposed of at the planned time, and the disposal value is unlikely to be much different to its written-down value.

The problem only arises when the value of assets and liabilities has to be formally brought to account in mid-life – and this is usually when the project does not pan out according to the original plan.

This was the situation with the reclamation liability mentioned in the example. The original reclamation provision was adequate on the assumption that the mine plan did not change. When the new owner adopted a different mine plan (because the mine would not have been a going concern with the old plan) suddenly the liability was under-provisioned by a factor of 10. In effect, the option to change the mine plan [i.e. the option that the new owner had] had a $9 million price tag not provided for by the seller.

Is it possible to design a valuation scheme for assets and liabilities that correctly takes into account the value of these real options? … the answer is no. The reason has to do with the amount of real capital within the business.

Even in an Ideal World Real Capital (Value) has a Problem

Most capital-intensive enterprise works in markets that are far from the ideal of economic theory, but if a reliable scheme for valuing assets exists it is more likely to be in this ideal world. Let’s consider this contestable market first. In such a market:

- there are no barriers to entry or exit,

- there are no transaction costs,

- there are lots of producers and consumers (no one buyer or seller can influence the market price of the product – it is a constant as far as any one producer is concerned) and

- there are well-defined market prices not only for the product being sold but also for all of the capital goods that make up the production process.

Surely, you might think, in this style of market the value of assets can always be accounted for in a robust way? Unfortunately, even in this ideal case, the answer is no. The example is again drawn from my book Capital and Uncertainty.

In this example an initial investment of $100 is made in production machinery which produces one widget per year over its expected and actual six-year life. For simplicity, and because the focus is just on capital, labor and other operating costs are assumed to be nil – the selling price is only related to the “capital” component of the cost of production.

In this ideal example, the assumption is that if the production machinery had to be sold at any time it could be disposed of at market price. In this example the market price declines at 25 per cent per year. At the end of the six-year term the machine is sold for scrap at its market value. Taxes are payable at an assumed 35 per cent rate, and depreciation allowances for tax purposes reflect market-based valuations.

The cash flow for such a case is set out in Table 1. It uses a discount rate of 15 per cent which is assumed to be consistent with uncertainties surrounding the project, and the “annual revenue” (“required” selling price of one widget) has been calculated so the NPV is zero. In other words, at this selling price the company is achieving a 15% internal rate of return on the funds invested.

Table 1 – Cash Flow for Market or Internal-to-the-Firm Value

Widgets produced by old machinery are indistinguishable from widgets produced by new machinery, so a constant unit selling price has to apply over the full life of the machinery. This calculated unit price (or annual revenue) of $29.32 is shown on the first line of the table.

The internal-to-the-firm value (the last line of the table) has been calculated year-on-year as the present value of the expected future cash flows from that year on.

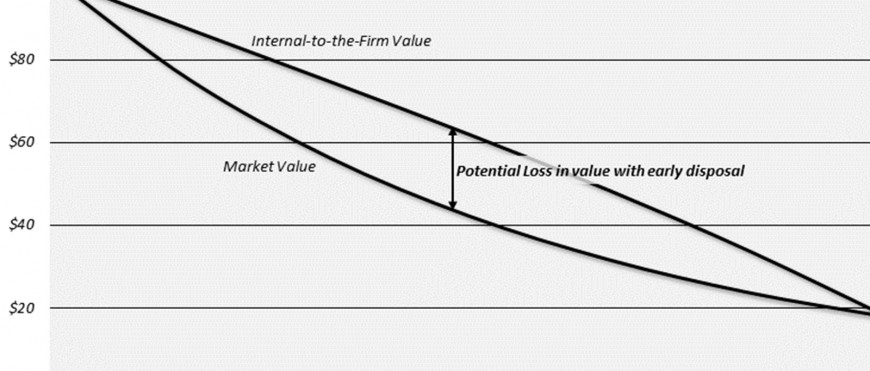

Figure 1 shows the internal-to-the-firm value and the market value through the life of the equipment based on the information in Table 1. Except at the start and end of the machine life the internal-to-the-firm value, based on the present value of expected future cash flows, is always higher than the market value.

Figure 1 – Market Value and Internal-to-the-Firm Value

In most real world applications there is an immediate drop in market value the day after delivery, due to transactions costs or information asymmetries. (In the earlier paper in this series the example of a motor vehicle was of information asymmetries). In Figure 1 these real-world effects have been excluded. Further, the cash flow explicitly accounts for depreciation in line with market prices and builds this cost (and the tax benefit) into the price, thereby removing the distortion due to this effect. Yet despite this, the internal-to-the-firm value, established by discounting future cash flows, still diverges from the market value. How can this be?

The apparent inconsistency comes about because the producer is effectively undercharging in the early years of project life when equipment is new, and overcharging in the later years when equipment is old. Producers are not doing this deliberately – a competitive market requires such a pricing strategy when there is no market-recognized difference in product whether it is produced by an old or a new machine. So whilst there is no real capital initially (you could sell the machinery the day after purchase and get all of your money back) the nature of this style of investment is that the amount of real capital increases throughout the first half of the life of the project (and decreases in the second half of the life of the project).

The owner’s exposure reduces throughout the life of the project when looked at from a total capital perspective. Exposure also reduces for the financial capital component. But in this example – typical of most mining investments – the real capital component increases through the first half of the life of the project.

A much better, and lower cost strategy (indeed, about 45% lower cost) to produce widgets over a 6-year period would be to buy a 3-year-old machine purchased on-market, and use it for 3 years, and then replace it with another 3-year-old machine kept for another 3 years.

Unfortunately this strategy lacks sustainable foundations. The flaw in such a strategy is that 3-year-old machines exist only because someone purchased them new and then disposed of them after 3 years. In a competitive market rational business people are unlikely to do this because such a strategy will increase their costs (price of widgets needed to get their required return on investment). In this case, the cost is higher by 34%. So if there is second-hand equipment available it will only be as a result of some out-of-the-ordinary sale. Any market price for equipment other than for new equipment, or for worn-out equipment, cannot be relied upon. Even if prices in this market are unambiguous, the volume will be too small to rely upon for any long term business strategy or as an exit strategy in the event of plans not going to expectation.

Thus, with this style of capital investment, even with well-established market prices, and even in a near-perfect market, asset valuation in mid-life is largely meaningless. If the project proceeds according to plan then valuations will only be brought to account at the end of the project and at that time there will be no problem. But any change of plan that causes valuations to be brought to account part-way through project life will invariably result in write-downs, if not in a tax-value sense, then certainly in the sense of a failure to achieve expected returns.

Nature of Mining Industry Capital

Many industries are capital intensive, and asset valuation issues like these are not unique to mining. Yet mining and a few other industries seem uniquely susceptible to perennially poor returns to investment (punctuated on rare occasions by periods of exceptionally good returns). Why is this so? Why are returns perennially poor? Why is it that seemingly the inefficient players aren’t being weeded out by market forces?

There is one simple reason, and two subtle reasons, why this is so.

Firstly, the simple reason, directly from the elementary economics textbook. Over-investment in any industry results in over-production. For demand to match supply then prices have to fall. Whilst the whole industry is affected by the price declines, it is the higher cost, least efficient operators who will fail. But this alone will not solve the over-investment problem. For the price mechanism to do its job the productive capacity of the failed producers must be taken off the market.

In the mining industry (and a few other industries) the productive capacity does not disappear. The equipment doesn’t go anywhere. It is too application-specific. It merely moves into the hands of some other player who continues to produce from a lower-capital-cost starting point. Even if the productive capacity does come off the market at the clearing (market) price, it will likely come back on the market as soon as the price once again rises. The assets are of little or no value in any other application – so will continue to produce so long as they are returning cash. Even in the situation of negative cash flow, production can continue if the owner (being sufficiently well capitalized) has the expectation that prices will recover in some manageable period of time.

For the mining industry, the major error is in over-investing in the first place.

The two subtle reasons have to do with why the mining industry, or certain sectors of the mining industry, along with certain other capital-intensive industries, are particularly prone to over-investment.

- Our cash flow models do not discriminate between financial and real capital. Under a rule focused on real capital certain styles of investments (with low proportions of real capital, regardless of the total capital) but with superficially low rates of return on total capital would go ahead whereas nple DCF assessment, they appear to show inadequate returns. Alternatively, other styles of investments that now superficially appear to show excellent returns would have to be restructured, changed, or simply not proceeded with.

- Investment decisions of this nature are NOT like consumer goods decisions. The investment decisions classically regard the plan as fixed, and take only scant account of the ability or inability of the plan to change during implementation. Thus the decision to expand or contract (i.e. to determine the optimum production rate) is radically different if made before capital is sunk when capital costs have to enter the decision and after capital is sunk when most capital costs do not enter the decision. The correct approach, prior to capital being sunk, must be to take into account what the decision-making forces are likely to be after capital is sunk. Or, again paraphrasing Arrow (1958) “an actor’s private formation of value must consider the relation between the action taken at any time point in the future and the information available at that time, though not available at the time at which the initial decision is made”.

We can now understand why these styles of businesses are subject to the poor returns:

- The industry is capital intensive – operating costs represent only a small proportion of the overall average cost of production.

- Whether it is produced by a new machine or an old machine, the characteristics of the product, and value to the customer, are the same.

- Any susceptibility to overproduction that results in idiosyncratic non-worn-out equipment coming on to the market even at well-established market prices will result in disruption of industry capital structure and erosion of returns for all players.

There are other industries similar to mining in this respect, but few that are as constrained. Some of these industries have come a long way to resolving these problems and there are lessons to be learned. This is a subject for another article.

About the Author

IanRunge

https://ianrunge.com